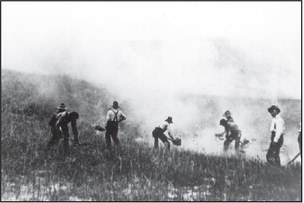

In the Middle of a Prairie Fire, 1876

Prairie fires were an ever-present danger in frontier Nebraska. Rolf Johnson of Phelps County knew this from experience. The Swedish immigrant provides a vivid description of one in his diary. His entry of November 10, 1876, describes "miles and miles of level prairie burnt black by a prairie fire." He continues: "Justus [Rolf's brother] and I were down on the Platte after wood and while on the island we suddenly heard a roaring, rushing, crackling sound and on investigating found the whole valley between us and Williamsburg [Phelps County] in flames, which sometimes leapt upward to a height of 30 feet or more. On driving out from the island we came near being scorched by the fire. . . .

"In one place we saw a big jackrabbit surrounded by a wall of fire on every side. He jumped about from side to side trying to find some outlet to his fiery prison, which was getting smaller every moment. I jumped from the wagon thinking to have roasted rabbit as soon as the flames had passed over him. Just as the flames closed about him and were about to swallow him up he cleared [the] burning barrier with a desperate leap and came near alighting on me. He was a moment blinking his eyes at me as if to say: 'How is that for high?' and then struck a bee line for the river to cool off his scorched skin." Johnson's entry for October 20, 1878, concerns another prairie fire: "This afternoon the prairie fire, driven with the speed of a race horse by a hard wind, came down from the north and came near sweeping everything before it. The flames leaped skywards, roared like a hurricane, the long dry grass crackled like musketry and the smoke obscured the heavens, and the air was hot as the blast of a furnace." Johnson says that he and several other men "saved Halin's place by means of back fires. It was in imminent danger a while and we had to work like fun." Other men "rode down to Aug. Jacobson's to try and save his place as he was not at home, but they could not stem the resistless sea of flames and very narrowly escaped a fiery death, their horses being singed and Aug. losing his coat." Johnson's diary has been published as Happy as a Big Sunflower: Adventures in the West, 1876-1880, by the University of Nebraska Press. The original diary is at the Phelps County Historical Society in Holdrege.

The Lincoln Chicken War

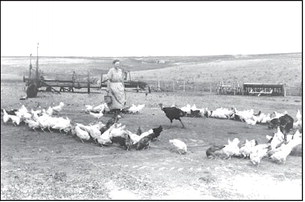

Sometimes it takes a good guy with a chicken to stop a bad guy with a chicken. Consider this strange tale about the founder of today's Lincoln Journal Star and his revenge on his hen-raising neighbors.

Town and city residents used to keep chickens and even milk cows on their property. On April 12, 1890, journalist J. D. Calhoun of the Lincoln Weekly Herald told a story that he attributed to Charles H. Gere, publisher of the Nebraska State Journal (and future namesake of Lincoln's Gere Library): "For some years after I was married I tried to do a little gardening both for the exercise involved and the product of the labor. I was greatly annoyed every spring by the ravages of my neighbors' hens. I shooed them out, I remonstrated with their owners, I threw rocks, I built fences, I bought a trained dog, but all in vain. All summer I planted and hoed and watered in vain. . . .

"Finally I began to dream of revenge and an inspiration came to me. That spring I planted no garden, but I went to a butcher and had him select for me three dozen of the oldest and biggest Cochin hens he got into his shop. It was a fine lot, not one in it that weighed less than 10 pounds. Just at the right juncture in the spring I had them put in my barn. The quarter in which I live was more village-like than it is now and all my neighbors had more or less garden as well as chickens. They also had children who minded them off the gardens-except mine.

"Just when all the garden stuff was in a fair state of early growth, tender succulent and tempting to hens, when the children were all at school the men down town and the women busy, I opened my barn door and turned out my hens . . . I had inadvertently forgotten to feed or water them for three days, and within 20 minutes after they were released there wasn't a green thing above ground within half a block of me. I collected my hens into the barn without attracting attention, and when the ravages were discovered each neighbor attributed it to the chickens of the other. Next evening there was a neighborly mass meeting, and a good deal of excitement, but a solemn agreement was made and ratified never, never, to keep any more chickens. I had the butcher come up and haul mine away after night, and to this day the people in the vicinity of J and Seventeenth [in Lincoln] don't know to whom they owe their deliverance from the chicken scourge." Did it really happen that way? Or was it just an amusing story? It's hard to say, but it speaks to a genuine movement in that era to regulate the presence of farm animals within city limits.

Arsenic in the candy: poisoning sensation in Hastings "The central figure in the Hastings poisoning sensation is Miss Viola Horlocker, a popular young woman of that town, who has made many visits to this city and is well known here," said the Kearney Daily Hub on April 14, 1899. The Hub noted that Horlocker, who enjoyed a local reputation as an amateur singer, had been employed as a stenographer for the last two years in the office of a Hastings law firm. She was accused of sending the wife of her immediate supervisor and sweetheart, Charles F. Morey, a plate of homemade candy laced with arsenic.

The candy, sent anonymously, arrived at the Morey residence on April 10, 1899. Mrs. Morey, and a friend who also sampled it, became seriously ill but survived. The Hub said on April 14 that "the circumstances implicate Miss Horlocker sufficiently to justify the prosecuting attorney in authorizing a warrant for her arrest." On April 13 she was charged with the poisoning in Adams County District Court. John M. Ragan, a former Ne-braska Supreme Court justice, was hired to head her defense team.

The sensational story of a starcrossed love affair and attempted murder was soon picked up by newspapers across Nebraska and received national attention. The New York Times on March 22, 1900, under the headline "Candy Poisoner on Trial," noted: "The defense created somewhat of a sensation by stating that Miss Horlocker was driven to insanity by the treatment of Mrs. Morey's husband, by whom she was employed, and was not responsible for her acts." The Hub on March 24 reported the courtroom testimony of Eva Stewart, who "detailed a succession of startling admissions made to her, . . . in which Miss Horlocker set forth her blind passion for Morey, and gave the story of his attentions to her, which had resulted in taking her affections out of her own keeping." Viola Horlocker also took the stand in her own defense. The Hub reported on March 27 that she "was very much agitated and wrung her hands continually, momentarily varying it by nervously rubbing her palms with her handkerchief. She described how Lawyer Morey invited her to his house in the absence of his wife and many love passages between them. . . . Her tears flowed freely during the recital." After only an hour's deliberation, the all-male jury came back with a verdict of not guilty. The Hub on March 30 said: "The verdict was generally expected and will be satisfactory to a majority of the people here, for reasons that are not necessary now to put in print." The Courier (Lincoln) on April 7 noted that Morey's conduct had "incensed and disgusted" the jury, which "not being able to punish him let Miss Horlocker escape the more readily." Putting the sensational trial behind her, Viola Horlocker reportedly left Hastings after her acquittal and settled in New York, where she later married. Charles Morey remained in Hastings, where he died in 1920, having regained the respect of many there. The Hastings Daily Tribune on May 5, 1920, reported that his funeral was attended by numerous friends, including members of the Adams County Bar Association.

Feeding free-range chickens

Fighting a prairie fire in Thomas County in the Sandhills, 1890.